Toward Unparenting

In the New Yorker, Elizabeth Kolbert surveys a crop of “unparenting” books that take aim at parental overproviding and overprotecting:

In the New Yorker, Elizabeth Kolbert surveys a crop of “unparenting” books that take aim at parental overproviding and overprotecting:

Madeline Levine, a psychologist who lives outside San Francisco, specializes in treating young adults. In “Teach Your Children Well: Parenting for Authentic Success” (HarperCollins), she argues that we do too much for our kids because we overestimate our influence. “Never before have parents been so (mistakenly) convinced that their every move has a ripple effect into their child’s future success,” she writes. Paradoxically, Levine maintains, by working so hard to help our kids we end up holding them back.

“Most parents today were brought up in a culture that put a strong emphasis on being special,” she observes. “Being special takes hard work and can’t be trusted to children. Hence the exhausting cycle of constantly monitoring their work and performance, which in turn makes children feel less competent and confident, so that they need even more oversight.”

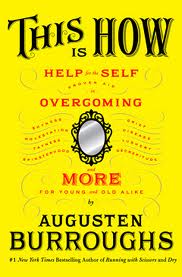

This is How

A self-help book for the self-help averse from Augusten Burroughs. Here’s a chunk, excerpted at TNB Nonfiction:

A self-help book for the self-help averse from Augusten Burroughs. Here’s a chunk, excerpted at TNB Nonfiction:

Canadian researchers found those with low self-esteem actually felt worse after repeating positive statements about themselves.

They said phrases such as “I am a lovable person” only helped people with high self-esteem.

The study appears in the journal Psychological Science…They found that, paradoxically, those with low self-esteem were in a better mood when they were allowed to have negative thoughts than when they were asked to focus exclusively on affirmative thoughts…”Repeating positive self-statements may benefit certain people, such as individuals with high self-esteem, but backfire for the very people who need them the most.”

And it was all so perfectly clear. No wonder I had found that woman so offensive. Sometimes things feel that bad.

Sometimes you just feel like sh!t.

And telling yourself you feel terrific and wearing a brave smile and refusing to give in to “negative thinking” is not only inaccurate -dishonest- but it can make you feel worse.

Which makes perfect sense. Because if you want to feel better, you need to pause and ask yourself, better than what?

Better than how you feel at this moment, perhaps.

But in order to feel better than you feel at this moment, you need to identify how you feel, exactly.

It’s like this: if California represents your desire to “feel better,” you won’t be able to get there -no matter how many maps you have- unless you know where are starting from.

Finally, trained researchers in white lab coats with clipboards and cages filled with monkeys had demonstrated in a proper clinical setting what I myself had learned several years earlier in a rehab setting: affirmations are bullsh!t.

Procrastination and Other Habits

Power of Habit author Charles Duhigg weighs in on Bloggingheads:

Runner’s High, Exerciser’s Brain

Science of the runner’s high and rats on running wheels in the New York Times:

Science of the runner’s high and rats on running wheels in the New York Times:

As the name suggests, endocannabinoids are chemicals that, like cannabis in marijuana, alter and lighten moods. But the body produces endocannabinoids naturally. In other studies, endocannabinoid levels have been shown to increase after prolonged running and cycling, leading many scientists to conclude that endocannabinoids help to create runner’s high.

The Cohabitation Effect

Couples living together out of convenience–“sliding, not deciding”–gets roughed up in the NYT by psychologist Meg Jay, author of The Defining Decade:

Couples living together out of convenience–“sliding, not deciding”–gets roughed up in the NYT by psychologist Meg Jay, author of The Defining Decade:

Sliding into cohabitation wouldn’t be a problem if sliding out were as easy. But it isn’t. Too often, young adults enter into what they imagine will be low-cost, low-risk living situations only to find themselves unable to get out months, even years, later. It’s like signing up for a credit card with 0 percent interest. At the end of 12 months when the interest goes up to 23 percent you feel stuck because your balance is too high to pay off. In fact, cohabitation can be exactly like that. In behavioral economics, it’s called consumer lock-in.

Relationship Help

For couples going through a rough patch, here’s a short video sampling of Getting the Love You Want author Harville Hendrix’s take on what draws people to each other and how to make a relationship work (short version: “be nice”). Lots more detail in the book.

Being Creative

Jonah Lehrer’s new book, Imagine, excerpted in the Wall Street Journal:

[C]reativity is not magic, and there’s no such thing as a creative type. Creativity is not a trait that we inherit in our genes or a blessing bestowed by the angels. It’s a skill. Anyone can learn to be creative and to get better at it. New research is shedding light on what allows people to develop world-changing products and to solve the toughest problems. A surprisingly concrete set of lessons has emerged about what creativity is and how to spark it in ourselves and our work.

Including…

Although we live in an age that worships focus—we are always forcing ourselves to concentrate, chugging caffeine—this approach can inhibit the imagination. We might be focused, but we’re probably focused on the wrong answer.

And this is why relaxation helps: It isn’t until we’re soothed in the shower or distracted by the stand-up comic that we’re able to turn the spotlight of attention inward, eavesdropping on all those random associations unfolding in the far reaches of the brain’s right hemisphere. When we need an insight, those associations are often the source of the answer.

[Update: Being too creative–book pulled.]

Therapists on Couples Therapy

Couples Therapy through the eyes of couples therapists in the New York Times.

“For starters, there’s an ever-present risk of winning one spouse’s allegiance at the expense of the other spouse’s,” explains William J. Doherty, the University of Minnesota professor of family social science, in his groundbreaking 2002 article on the topic of awkward couples counseling in the Networker, titled “Bad Couples Therapy.” “All your wonderful joining skills from individual therapy can backfire within seconds with a couple. A brilliant therapeutic observation can blow up in your face when one spouse thinks you’re a genius and the other thinks you’re clueless — or worse, allied with the enemy.”

The Power of Habit

NYT previews The Power of Habit–a look at the latest thinking about how habits are formed (and how that knowledge helps sell diapers and Fabreze).

NYT previews The Power of Habit–a look at the latest thinking about how habits are formed (and how that knowledge helps sell diapers and Fabreze).

The process within our brains that creates habits is a three-step loop. First, there is a cue, a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use. Then there is the routine, which can be physical or mental or emotional. Finally, there is a reward, which helps your brain figure out if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future. Over time, this loop — cue, routine, reward; cue, routine, reward — becomes more and more automatic. The cue and reward become neurologically intertwined until a sense of craving emerges. What’s unique about cues and rewards, however, is how subtle they can be. Neurological studies like the ones in Graybiel’s lab have revealed that some cues span just milliseconds. And rewards can range from the obvious (like the sugar rush that a morning doughnut habit provides) to the infinitesimal (like the barely noticeable — but measurable — sense of relief the brain experiences after successfully navigating the driveway). Most cues and rewards, in fact, happen so quickly and are so slight that we are hardly aware of them at all. But our neural systems notice and use them to build automatic behaviors…

Why Are Older People Happier?

Science seeks answers. A couple of possibilities:

[S]tudies have discovered that as people age, they seek out situations that will lift their moods — for instance, pruning social circles of friends or acquaintances who might bring them down. Still other work finds that older adults learn to let go of loss and disappointment over unachieved goals, and hew their goals toward greater wellbeing…